Long ago I responded to some objections against desire satisfactionism that have been raised by Russ Shafer-Landau in The Fundamentals of Ethics. I wrote more responses, but I never posted them. So here they are. Desire satisfactionism is good!

All the block quotes are counterexamples raised by Shafer-Landau. Here’s the first:

The first is that of pleasant surprises. These are cases in which you are getting a benefit that you didn’t want or hope for. Imagine something that never appeared on your radar screen—say, a windfall tax rebate, an unexpectedly kind remark, or the flattering interest of a charming stranger.

You didn’t want the thing, then you get it, and now that you have it you want it. So you have an additional instance of desire satisfaction that you did not expect. What’s the problem? Maybe RSL thinks the problem is that it’s good for you as soon as you become aware of it, without any delay. I’m inclined to disagree, but even if I didn’t there’s no problem here. You may begin desiring it, in the relevant sense, before you even know you have it — so there needn’t be any delay between knowing you have it and its being good for you.

The second case is that of small children. We can benefit children in a number of ways, even though we don’t give them what they want and don’t help them get what they want.

These are instrumental benefits. Teaching a toddler to use the toilet may not satisfy their desires now, but it avoids serious desire frustration down the line.

The third case is suicide prevention. Those who are deeply sad or depressed may decide that they would be better off dead. They are often wrong about that. Suppose we prevent them from doing away with themselves. This may only frustrate their deepest wishes. And yet they may be better off as a result.

More instrumental benefits — trading one desire frustration (no suicide) for a boatload of future desire satisfactions (that they can have because they will be alive).

In each of these cases, we can improve the lives of people without getting them what they want or helping them to do so. They may, later on, approve of our actions and be pleased that we acted as we did. But this after-the-fact approval is something very different from desire satisfaction. Indeed, it seems that the later approval is evidence that we benefited them, even though we did not do anything that served their desires at the time.

We did benefit them, instrumentally. If my parents hadn’t taught me to read, my present illiteracy would frustrate many of my desires and prevent me from satisfying others. Thus, they benefited me.

Sometimes we want something for its own sake, but our desire is based on a false belief. When we make mistakes like this, it is hard to see that getting what we want really improves our lives. Suppose you want to hurt someone for having insulted you, when he did no such thing. You aren’t any better off if you mistreat the poor guy. Or perhaps you desperately want to be popular with a certain group of people, but only because you think that they are glamorous and happy. Once you get to know them better, you come to realize how shallow and miserable they are. As the old saying goes: beware of what you wish for—it may come true.

The issue here is how to figure out the contents of peoples’ desires. Suppose I am desperately trying to grab this shiny piece of fool’s gold. Then I grab it, realize it’s not real gold, and chuck it away. The question is: did I want (i) that rock, or did I want (ii) gold? If (i), then my desire was satisfied; if (ii) then my desire was frustrated. The only interpretation that makes trouble for the DSist is (i)&~(ii). But that’s the only interpretation that is antecedently implausible. I’m not entirely sure how to answer, but it’s got to be either (i)&(ii), or ~(i)&(ii). I clearly didn’t get gold, and gold is clearly at least part of what I wanted.

It’s the same with RSL’s cases. At least part of what you want is to hurt whomever insulted you, and be popular with glamorous and happy people. Those desires aren’t satisfied, they’re frustrated. So at best it’s a wash — you get something you wanted (to beat up that particular guy and fit in with that particular group of people) and you fail to get something you wanted (hurt people whomever insulted you, and be popular with glamorous and happy people).

A few years ago I read about a whale that had beached itself on a New England coast. I remember wanting that whale to survive, to be eased back into the ocean without being harmed. And it was. It’s easy to see that the whale was better off as a result of the rescue operation. But it’s not so easy to see that my life got any better.

This is the first objection which troubles me as a desire satisfactionist. I agree it’s unintuitive that the success of the rescue operation increased RSL’s well-being. But I think that there are good reasons to think that it’s true, and good reasons to expect that it would sound weird even if it is true.

Start with the reason why it would sound weird even if true. RSL’s statement about his own well-being sounds weird because it implies something false — namely that the increase to RSL’s well-being is substantial enough to be worth mentioning, relative to other salient factors. The implication is false because in the present context we’re talking about a massive benefit to the whale. That benefit is highly salient, and by comparison the benefit to RSL is not at all important.

To make the point more vivid, suppose I tell you the following: “I saw a guy get hit by a bus today. I was hoping he would dodge in time but he didn’t. Apparently he will be paralyzed and endure chronic pain for life. So that really ruined my day!” My bizarrely callous speech is literally true. DSists and non-DSists should agree that the stress of seeing someone get hit by a bus is bad for me. But it’s not worth mentioning compared to the (highly salient) reduction in well-being to the guy that actually got hit! And that makes it sound very weird. I think that’s at least part of what’s going on in the whale case. It’s like saying “Global warming will have benefits for humanity” or “Elon Musk owns more than $1,000 dollars.” Technically true, but with false implications.

Okay, so that’s how it might sound weird even if it’s true. But why think it’s true? Here is the line of thought that moves me. I start with the thought: what would be the absolute perfect life for me? If I think of all the possible worlds in which I exist, which world and life is best for me? Getting specific about my answers makes me think that it’s better for me if beached whales are be rescued.

First specific question: would the best world or life be one in which I’m dreaming or plugged into a machine that’s giving me lots of great experiences? Answer: no. I endorse the experience machine objection. A life in the experience machine might not be terrible, but an even better life would be one in which I have all those great experiences as a result of real accomplishments, relationships, parties, etc.

Second specific question: what about the other people in this world? Granted that they have to be real, as opposed to the products of a dream or an experience machine. But can they be actors, or automata, or do they have to be real people too? Answer: they have to be real, too. If we’re comparing a world in which I’m partying with actors/automata, versus a world in which I’m partying with real people, the second world is better for me — even if I can’t tell the difference. This is really just iterating on the same intuition as I and many other people have in response to the experience machine case. It’s better to have the real thing rather than an illusion, even if the illusion is so good you can’t tell the difference. In this case the real thing means real people as opposed to actors or automata.

Third specific question: granted that the other people in this world have to be real, should they be happy? Or is it okay for there to be lots of miserable people, provided they don’t impinge on your wonderful life? Answer: they have to be happy. A world that’s perfect for me has to be a paradise, so that there’s nothing for me to worry or feel guilty about. Nice guy that I am, I sometimes worry about other people. If God were to make the world perfect (for me) he would have to change everything that worries or troubles me, and that includes other people’s worries and troubles. Again, it’s not enough for there to be a convincing illusion that there’s nothing for me to worry about; there has to really be nothing for me to worry about. It follows that, if God were creating a perfect world for me, he would have to make everyone happy. God would have to do this for my sake, as part of his general program of making the world a paradise for me.

Of course, if I were a psychopath that didn’t care about other people and animals, then things would be different. But I'm not a psychopath, so I do worry about other people and animals, and so if God were making me a paradise he would have to take other people and animals into account — again, for my sake.

Once again this sounds weird. It is to talk about everyone else being happy purely in terms of how it benefits me, because it’s creating the false implication that others’ happiness benefits me in a way that is worth mentioning, relative to the highly salient benefit they enjoy. This implication is false, but irrelevant to the present question. So we have to be careful to ignore the false implication, and think only about the claim that other people’s happiness benefits me. I think that, insofar as I accomplish this, I do have the intuition that other people’s happiness benefits me. An ideal environment/world for me would be one in which (in addition to my own incredible happiness) everyone else is happy, too. Insofar as people (and animals) are not happy, this is a departure from my ideal life.

So, I do think this is a better objection than the others thus far, but in the end I think the objection can be met.

There is a natural reply to such examples. My life was indeed mildly improved, because I was pleased to get what I wanted. And that may be true. The problem with this reply, however, is that it is not available to desire theorists, since they do not assign any intrinsic value to pleasure.

This is a weird reply to suggest on behalf of the DSist, since a real DSist would say that you’re benefitted whether or not you know that the whale was okay. But in any case, many DSists think that pleasure is reducible to desire satisfaction, so all pleasures do have intrinsic value because they are instances of desire satisfaction.

But consider a young musician who has staked his hopes on becoming famous some day. And that day comes—but all he feels is disappointment. He got what he wanted. He knows it. And he hates how it feels.

This is just the opposite of the original surprise case. You wanted the thing, then you got it, and now that you have it you don’t want it. So there’s no desire satisfaction here, at least so long as the desire and the thing that satisfies it must be contemporaneous. It’s just this sort of case that makes me think they do need to be contemporaneous. Intuitively, there was never a point at which you had what you wanted. There was a point in which you wanted something and didn’t have it, and a point at which you had something but didn’t want it, but no point at which you had the thing and wanted the thing.

…think of a man who very much wants to be a father. He has a series of relationships, one of which leads to a pregnancy and then to a child. But the mother never informs him of this, and he never finds out through other channels. His desire is satisfied, but his quality of life has not improved.

If this guy’s desire really is satisfied, then his desire is bizarre. Usually, when someone says they want to be a father, they don’t mean “impregnate someone and pass off my genetic material”. They want to actually raise a child and do fatherly things. That desire isn’t satisfied, so the person RSL describes must have the bizarre desire.

Bizarre desires might also be thought to pose a problem for DSism, quite apart from the issue of ignorance that RSL raises here. In the interest of dealing with one problem at a time, we can construct a different case that raises the concern about ignorance, without involving any bizarre desires.

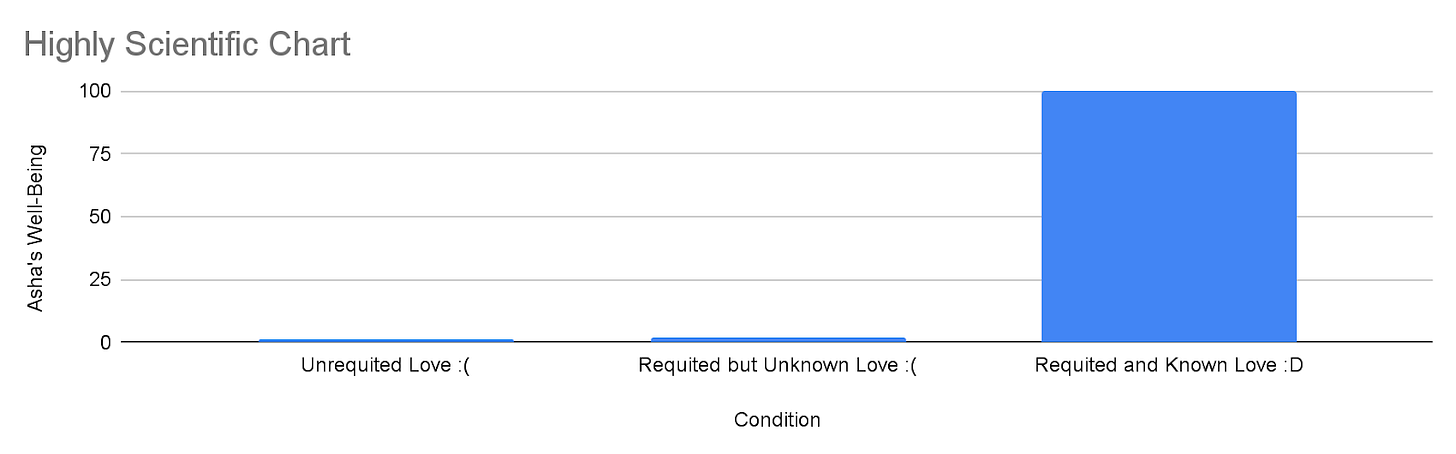

With that in mind, suppose Asha is in love with Bob, and wants to be loved by him in return. They are friends throughout their lives, romance never blossoms, and then they both die. Bummer! Now consider two different worlds in which two different versions of this story take place. In the first world Asha’s love was unrequited. In the second world Asha’s love was requited, because Bob was in the same situation all along: he loved Asha, and wanted to be loved by her in return. They just never discovered each other’s feelings. The question is: which world was better for Asha?

I think it’s natural to say: neither, they both suck for Asha! The first world sucks because of unrequited love, and the second world sucks because neither of them ever confessed their feelings! But again, I think this is partly because the difference between the worlds is tiny in comparison to a salient alternative: the world in which Asha and Bob do confess their feelings. The worlds look like this:

The difference between the first two worlds is negligible in comparison to the third world. We want to say: “Bob secretly loving Asha isn’t really good for her, because what would really be good for her would be if she actually knew that Bob loved her back.” But this is a bad inference. From the fact that the third world is far better than the first or second worlds, it does not follow that the second world is no better than the first world.

Again I find it helpful to think in terms of the question: “What would be the absolute best world and life for Asha?” Let’s suppose that the best world for Asha would be one in which she and Bob are in a loving relationship. Compared to the first world, the second world is a little closer to that ideal world for Asha.

I’m confused by what the desire satisfactionist means by 'desire'. As your responses to these putative counterexamples show, it can’t be people’s actual desires. But then what is meant by ‘desire’? The desire satisfactionist seems to be using the word ‘desire’ as a placeholder for what would make a person better off if this desire is fulfilled and worse off if it is not. But this tells us nothing about well-being. It is unclear what are the real, relevant desires or the kinds of things that make us better off/worse off.